Archibald McIndoe was a plastic surgeon during WWII who reconstructed the burned faces and hands of many RAF airmen. By his advocacy, he turned a small English town into a community that helped the disfigured airmen feel comfortable reintegrating into society. The town became known as “the town that did not stare”.

Trigger Warning — Some readers might find the following descriptions and pictures triggering.

Townspeople didn’t blink an eye when they saw a man whose face was bandaged in bizarre ways. They didn’t flinch when shaking hands with a man who had only two fingers. They didn’t stare at men whose appearance was abnormal. They didn’t stigmatize men whose behaviour was strange because of their traumatic injuries.

The entire town became a community where survivors of horrific injuries felt welcomed and safe whenever they socialised with the townsfolk. The townsfolk treated the survivors with respect. Better still, they honoured the survivors. They never treated the survivors as deficient or defective or weird.

Can you imagine an entire church treating survivors of abuse like this? Can you imagine a congregation being an encouraging and entirely safe place for survivors of abuse?

Can you envisage the congregation welcoming, respecting and honouring survivors of abuse who want to talk about their experiences and be validated, and who want never to be judged or shut down when they express their emotions? Can you imagine an entire Christian community that vindicates and honours abuse survivors for resisting their abusers?

As I learned about this town becoming a safe and welcoming community for survivors of violence, tears kept coming to my eyes. As I typed this post, tears rose again. The story inspired me but it also saddened me because I yearn for society to be a place where survivors of domestic abuse are never stigmatised, but rather are accepted, welcomed, embraced, and made to feel comfortable as they reintegrate into society after being traumatised by their abusers. How my heart yearns within me.1

Let me share with you the story of how Archibald McIndoe persuaded the small English town of East Grinstead to become a therapeutic community for his burned patients. Not only is this story touching and inspiring, it also has a personal flavour for me because my daughter is living in East Grinstead and I first heard this story when she visited the East Grinstead Museum and sent me photos.

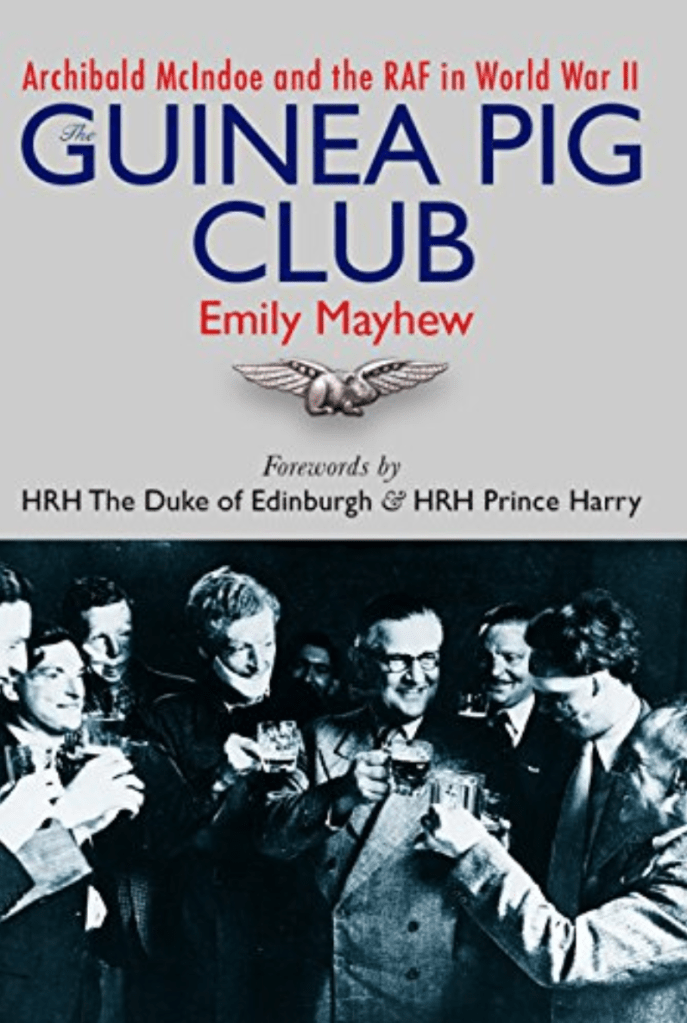

McIndoe developed skin grafting techniques that had never been used before. Archibald McIndoe’s patients were jokingly called “guinea pigs” and they decided to start The Guinea Pig Club.

The history of the Guinea Pig Club, the band of airmen who were seriously burned in aeroplane fires, is a truly inspiring, spine-tingling tale.

Plastic surgery was in its infancy before the Second World War. The most rudimentary techniques were only known to a few surgeons worldwide. The Allies were tremendously fortunate in having the maverick surgeon Archibald McIndoe nicknamed the Boss or the Maestro operating at a small hospital in East Grinstead in the south of England. McIndoe constructed a medical infrastructure from scratch.

After arguing with his superiors, he set up a revolutionary new treatment regime. Uniquely concerned with the social environment, or holistic care, McIndoe also enlisted the help of the local civilian population. He rightly secured his group of patients dubbed the Guinea Pig Club an honoured place in society as heroes of Britain’s war.

— The Guinea Pig Club by Emily Mayhew, Greenhill Books, 2018.

Skin grafting by tube pedicles

From The East Grinstead Museum website:

McIndoe had learnt the tube pedicle technique from fellow plastic surgeon, Harold Gillies. He went on to refine the procedure into a more effective skin grafting method for facial and hand reconstruction.

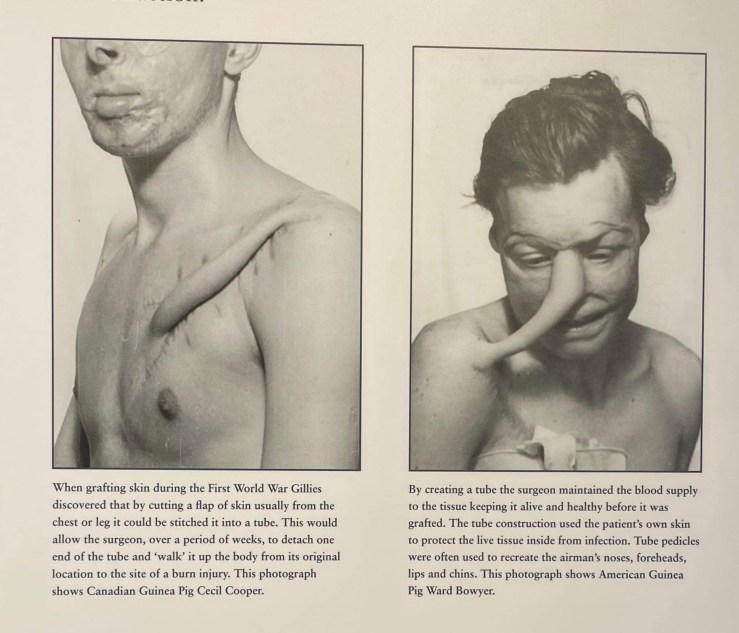

When grafting skin during the First World War, Gillies discovered that by cutting a flap of skin usually from the chest or leg it could be stitched it into a tube. This would allow the surgeon, over a period of weeks, to detach one end of the tube and ‘walk’ it up the body from its original location to the site of a burn injury.

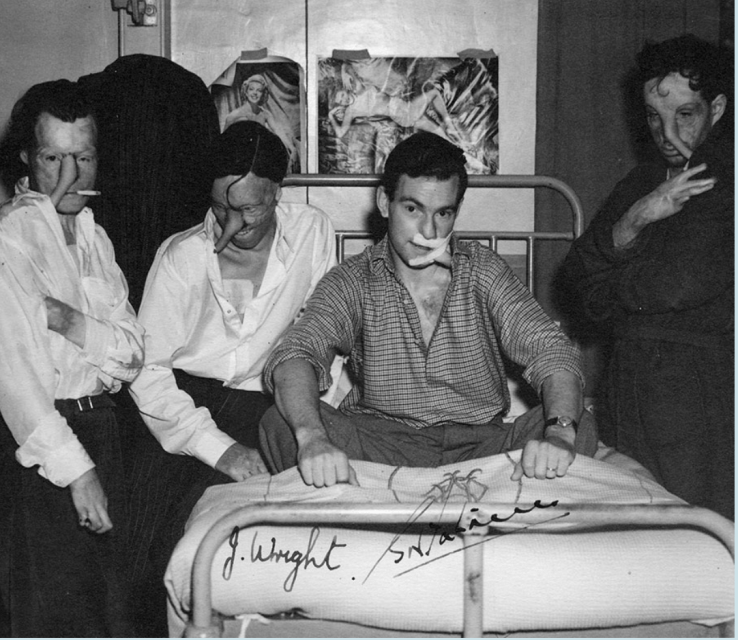

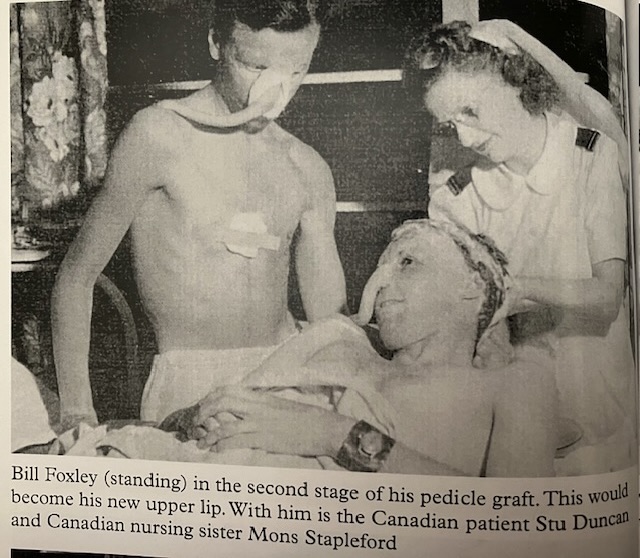

As the tube pedicle was moved up the body it took three weeks for the blood supply to establish itself in between grafts. This meant the airmen had to get used to holding themselves in awkward positions with restricted movement so as not to damage the pedicle. These men shown above are all waiting for their pedicles to be cut off their bodies and shaped into new facial features.

By creating a tube the surgeon maintained the blood supply to the tissue keeping it alive and healthy before it was grafted. The tube construction used the patient’s own skin to protect the live tissue inside from infection. Tube pedicles were often used to recreate the airman’s noses, foreheads, lips and chins.

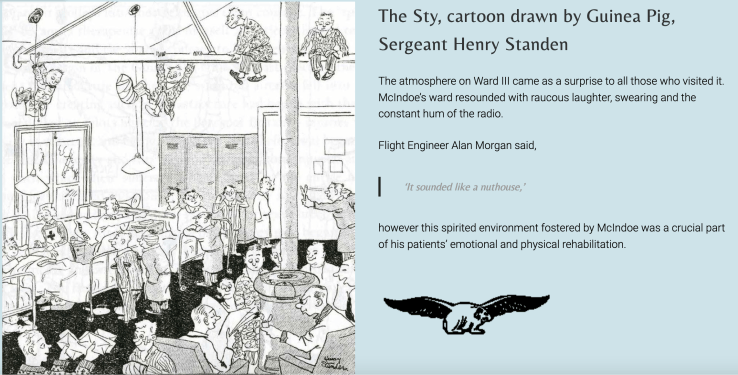

Unlike other wards, Ward III had its own piano encouraging socialising and singing amongst the men.

Crucially, McIndoe allowed a barrel of beer on the Ward, turned a blind eye to practical jokes, and encouraged flirting with the nurses.

As young men cut down in their prime, one can see how this approach could help to restore the Guinea Pigs’ masculinity and morale.

Source: eastgrinsteadmuseum.org.uk/guinea-pig-club/the-guinea-pig-club/

How the town of East Grinstead became a therapeutic community

Here some quotes from The Guinea Pig Club by Emily Mayhew, pages 209-241. My comments are interspersed between the quotes.

The process of integrating the facially disfigured into a variety of public contexts was not just a complex mixture of medical and military initiatives, it was, above all, a matter of human understanding and instinct. Nothing is more important or more difficult to manage than human instinct; the instinctive reaction to a severely disrupted human face is to be repelled, to turn away, to ignore. And it is in dealing with the matter of human instinct that the presence of Archibald McIndoe was crucial, for it was he who persuaded the public to turn back, to look his patients in the face, and then to begin the process of understanding what such men represented.

Human understanding and instinct. Most humans do not want to understand the deep traumas which domestic abusers inflict on their targets. When survivors talk, weep, show indignation, or express any strong emotion about their experiences, most humans feel uncomfortable — and they don’t want to (or can’t) offer the kind of non-judgemental presence which would comfort the survivors. Instead, they give un-asked for advice. Or they ignore the survivor’s visible signs and symptoms of distress and act like they are not happening. Or they judge, stigmatise, and patholigise the survivors. Some people do all three responses at different times and to different extents. See my article Unhelpful Comments by Well-Meaning People.

Most Christians ignore the instruction to weep with those who weep (Romans 12:15). I often wonder how they skip over this instruction. Don’t they ever ask themselves whether they are following that instruction? Don’t they ever feel bad for ignoring it? Don’t they feel even a twinge of guilt when they tell a survivor who is weeping to see a counselor? Don’t they realise that they are shirking their duty to simply weep with those who weep?

The question of relations between the severely burned patient group and their local, professional and national environments was an issue that needed to be resolved within months of the first ‘burned boy’ being received at East Grinstead. The location of the unit, in the centre of a small prosperous town 40 miles outside London, posed unique problems for McIndoe. Not only was he faced with, as he himself put it, ‘the opportunity of surgically restoring a large consecutive series of facial burns in which deconstruction has been massive’, and for which existing treatment methods were patently unsuitable — indeed even dangerous — he also had to resolve the situation in public. His patients who manifested such massive deconstruction were highly exposed to East Grinstead — contact with the townsfolk could not be avoided — and relations between the two parties require careful negotiation. Yet McIndoe’s management of those relations, and of the relations between the RAF casualties and the [RAF] service itself, was far more than a question of mutual accustomisation. He determined that the social environment in which the medical treatment took place was a crucial factor in the success of the repair. He therefore actively sought the participation of the public and the service in the treatment process, over and above securing their acceptance of the casualties among them.

McIndoe’s burned airmen were no ordinary patients; at first they were ‘the few’, the knights of the air, to whom so much was owed by so many. They were young and energetic, many with lifestyles and sports cars that matched their dashing reputation. Above all, once first aid and primary care had been administered, they were not bed-bound. Very many of Ward III’s patients had suffered only the external trauma of burning, and had few or no internal or orthopaedic injuries which would impair their mobility. The situation was the same regardless of the stage their reconstructive surgical schedule had reached — indeed patients mid-schedule could be even more challenging to the public gaze than those with only burns trauma, a situation McIndoe well appreciated:

‘… the immediate results are often more horrifying than the original condition until the resolving influence of time has softened their asperities and enabled movement, expression and texture to return.’

Such patients might have patchwork faces, or trunk-like tube pedicules from face to shoulder to graft a new nose or ear, but they could still walk, drive, drink and dance. Their boredom threshold was non-existent and, if they could not return to flying immediately, they wanted to return to a normal life and living environment as soon as possible. The very shortest of walks out of the hospital took them to East Grinstead, where could be found pubs, restaurants, a dance hall and cinemas.

Before civilians could contribute to the reconstruction process, both patient and public had to get used to each other. This meant getting the public into the hospital and the patients to resume their lives as comfortably as possible in public. Although this process has not been formally recorded, it appears that McIndoe himself addressed local worthies, hosted seminars and lectures at the hospital, and arranged concerts and sporting events in its grounds. He prevailed upon the ladies of the larger houses in town to visit the ward and its patients, to provide fresh flowers on a weekly basis, and to act as his ambassadors for East Grinstead’s population at large. The entire staff of the hospital were committed to this process. After their long shifts, East Grinstead nurses, many of them local, visited townsfolk to explain the medical work and its physical consequences, and to seek their co-operation and invitations for the patients into their houses.

Can you imagine this kind of educational advocacy being done in churches so that non-abused Christians would become accustomed to abused Christians being authentic in churches? Can you imagine congregations becoming safe and welcoming communities for trauma survivors? Can you imagine all the staff and influential people in the church being committed to this process?

A fair amount of initiative was taken by the citizens of East Grinstead themselves. Mabel Osbourne was a young waitress at the Whitehall restaurant when the first group of burn patients entered the restaurant. She nervously served them and, at closing time, joined a meeting of her fellow staff to discuss how they should handle such customers. Mabel remembered:

‘We sort of made up our minds about what we should do. [We thought] Oh let’s look at them — look them full in the eyes and just see them, and treat them as if we don’t see it. We’ll look at them and not look away from them and speak to them. And that’s what we did … and we got so used to it we never took any notice after that.

Other townspeople handled their introductions to McIndoe’s patients slightly differently from Mabel and her workmates. For a recent television documentary, Stella Clapton remembered her husband sternly turning to her as they were about to enter Whitehall saying, ‘Don’t you bat an eyelid when you go in, not an eyelid.’ Mabel and the Claptons were among the first to experience both the look and the practical hindrances of burn injuries, as described by Squadron Leader Bill Simpson in his memoir, The Way of Recovery:

… those first sorties into the world outside the hospital were painful, especially for the youngest among us. Without hands, for instance, it was impossible to do anything without assistance. It was embarrassing to have someone pouring beer down your throat, wiping your mouth, blowing your nose, handling your money. It was even more embarrassing to have to make for the gentleman’s cloakroom in pairs. Naturally no young adult man experienced such a loss of his independence without resenting it strongly, for it made him as helpless as a small child and robbed him of all his dignity.’

In particular, the resolution of Mabel and her friends regarding their new group of customers had such a positive effect that the Whitehall restaurant became an unofficial hospital social club, while the manager, Bill Gardner, became an unofficial member of the hospital welfare team:

‘Bill … took a special personal interest in our welfare. At the bar he would stand and drink with us, but he always had one eye on those of us who tended to drink too much. … Whenever we felt particularly conscious of being ugly and deformed, we always knew there was a welcome waiting for us at Bill’s, and that he would soon laugh away any tendency we had towards gloom or depression.’

Bill Gardner became so caring towards the burned airmen that they made him an honorary member of the “Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Guinea Pigs”.

The burned airmen’s experience was similar to — but different from — that of domestic abuse survivors. The burned airmen wanted to socialise and be accepted and do things they normally did when not on active duty in the airforce. Survivors of domestic abuse also want to socialise with non-burned people without being retraumatised.

The burned airmen wanted to be able to drink and laugh and tell jokes. But domestic abuse survivors, especially Christian survivors, seldom want to laugh and tell jokes. More often they want to talk about their trauma and be believed, vindicated and receive comfort from ordinary people. Rarely do they want to be cajoled or jollied out of sad and heavy feelings, because such cajoling ignores and dismisses the reality of their pain. When ordinary Christians use pat Christian sayings to buck up a despondent survivor, they are only pouring salt in wounds and conveying that the survivor’s trauma is not a valid part of the Christian life and they’d better put on their “shiny happy mask” if they want to go on socialising with Christians.

The Whitehall was part of a large entertainment complex in the centre of town which included a cinema and the Rainbow ballroom. Rather than discourage this strange and expanding customer group, the owners of the complex … followed the example set by their staff, and made McIndoe’s patients welcome. There were always seats in the cinema reserved for them and standing invitations to the weekly dances at the Rainbow. The Whitehall was Ward III’s outpost in the town, and when ‘a line with a nurse’ led to the altar, as it did with increasing frequency in East Grinstead and at the other RAF burns units, it hosted the wedding receptions.

McIndoe’s demands on East Grinstead were also practical. As well as providing everything from fresh garden flowers for Ward III to library books, he also asked that patients be received as guests and more by local families. Family houses with rooms to spare became unofficial convalescent homes.

Squadron Leader Bill Simpson remembered:

‘Many houses were thrown open to us. In them we were never allowed to feel in any way peculiar. We were treated as members of the family, and from the contacts we made friendships grew which are unlikely ever to be broken.’

Wives of burned airmen were also given room and board in townspeople’s houses when visiting their husbands. The host family would not accept payment or food coupons from the wife. Can you imagine this being done for survivors of domestic abuse who have to travel long distances to where their ex lives, in order to comply with court orders about child visitation?

As the burned RAF aircrew moved around East Grinstead, their acceptance into the community answered McIndoe’s challenge to the town to be a part of the therapeutic community. East Grinstead provided an initial first step between hospital ward and public life, easing the re-entry of the facially disfigured into society. The town had become a part of the medical team at the hospital. Accommodation became encouragement, affection and communal pride in what was perceived as the town’s unique contribution to the war effort. So successful was the relationship between town, hospital and patient group that patients were actively discouraged from going home to their families too early, and encouraged to remain in the therapeutic community which had been created. George Morely described the reasons for this in an RAF pamphlet on plastic surgery written during the war:

‘… Mental and moral rehabilitation demands serious consideration from the very instant that these patients commence treatment in the Centre. It is not usually advantageous to return these patients to their homes, unless they have domestic anxieties which they can alleviate, because the sympathy which they may receive may be misdirected and discouraging. It is usually more beneficial to proceed to active rehabilitation and to set the patient well on the road to full recovery, after which he should return to his family for a period. The idea here is to return him home when he is full of pride in his prowess, inclined to mix with his fellows and to show off his abilities, rather than prematurely to send him into an environment of sympathy instead of encouragement.’

Can you imagine the church being such an effective therapeutic community for survivors of abuse that it would probably be better for survivors to socialise within their congregation for some time, before going home to their family of origin? Some survivors have supportive families, but in my observation most do not. Many survivors’ extended families are very cruel, harsh and judgemental. And unsafe, because the abuser has recruited them as allies. Can you imagine a congregation being impervious to an abuser’s attempts to recruit them as allies, so the congregation was a far safer place for the victim than the victim’s own family? Isn’t that what Christians are meant to be for each other — family, brothers and sisters in Christ?

The contribution of the town was also acknowledged in the memoirs of the patients themselves. Squadron Leader Bill Simpson recalled in his memoir:

‘Here in this southern town there was never any suggestion that disfigurement should be concealed, and that the disfigured should be confined to hospital … quite the contrary. Inspired by Archibald McIndoe himself, we were encouraged to circulate freely, no matter how bad our physical condition appeared, and the result was complete success. I can only look back with horror at the examples that I had seen elsewhere in the past of attempts to conceal the disfigured. Here in this southern town, morale was kept high.’

In return for its commitment to the patients, East Grinstead gained national attention not only for the efforts of the doctors and patients in its midst, but also for its own efforts in bringing about successful recoveries.

The Readers Digest wrote in 1943:

‘… the townspeople know how to do their unparalleled job making the horribly burned RAF boys from the nearby Queen Victorian Hospital know they can still live in society. These lads with the shapeless raw, red faces come down to town. They don’t want to come at first. They walk down the street, trying not to see themselves in shop windows, their curled and sometimes fingerless hands in their pockets. Their faces are not of this world during the long period of skin grafting. Often the nose or both ears are gone. Their eyes are tiny, bleak, glistening marbles, and the look in them is not one to write about.’

‘The first time you see one of these boys the blood goes out of your face and your stomach rocks. You curse yourself but you can’t help it. But the good people of East Grinstead stop these chaps in the street and chat with them. They take them into their homes and give them tea. The girls invite them to dances. And not even the children stare at them. One obvious shudder might undo weeks of excruciating work at the QVH. So in East Grinstead the most ghastly burned boy is the most welcome. His face is the job of the hospital, but his will to live is a job that is in the hands of the townsfolk.’

East Grinstead had risen to Archibald McIndoe’s challenge to become a part of the therapeutic team dealing with the problem of the burned airman. In doing so it provided him with the evidence that the social environment in which surgical reconstruction took place was as important as the medical environment.

Don Armstrong was a boy when the war brought the burned airmen to the town and told how:

We as kids were very aware that they were heroes. We’d watched the Battle of Britain. We’d watched these guys operating over our heads and we had a very great affection for them.

They [the burned airmen] were amazing people. I remember, they’d shake your hand and you don’t flinch if the hand’s not a full hand. You just accept it otherwise a lot of them would have just gone home and not wanted to go out and meet people — but they were really fun people.” — Patricia Dyer, local resident. (This paragraph is copied from a photo my daughter sent me of the East Grinstead Museum display.)

Can you imagine church folk saying that abuse victims are ‘really fun people’? What a lot would need to change in churches for most professing Christians to have that view of us! For folks to see us as ‘really fun people’, they would need to be willing to listen to our emotions and weep with us, validate us, believe us, and stand with us in resisting the abusers. Then they would find what fun people we are to be with. How vibrant we can be when we are in safe surroundings with no fear of being misjudged.

Paul wrote, “O ye Corinthians, we pursue you with many words. Our hearts yearn to you. You are not shut out in us, but are shut away in your own selves.” (2 Corinthians 6:11-12 NMB)

Not much has changed since the Apostle Paul wrote that. Most professing Christians these days shut themselves away in their own selves, preferring to keep the Christian-Mask game going, rather than hear and heed the yearning pleas and laments of abuse victims.

McIndoe also advocated to the RAF and the British Government

He advocated to enable his patients to wear battledress uniform and receive full pay while they were receiving medical treatment.

The RAF did not allow its men to wear the RAF uniform if they were not on the active serving list.

Convalescents were allowed to wear ‘convalescent blues’ — a crude approximation of battledress in calico, more akin to the prison yard than to the hospital ward.

McIndoe simply ignored that regulation. (Three cheers for McIndoe!) He allowed his RAF patients to wear their battledress uniforms, and he left the boxes of ‘convalescent blues’ unopened in the hospital storeroom. Wearing battledress made a big difference to the men’s dignity, especially when they went into town.

McIndoe successfully pressured the RAF to change its regulations so that his patients did not have to wear ‘convalescent blues’. One of the arguments used in that advocacy was that:

There was no parallel in the Services to aircrew who fought the enemy with hundreds of gallons of petrol on board … the fire risk was greater than in any other part of the Service … It was generally recognised that aircrew personnel were selected from the finest material and this was another reason for special treatment.

What does it mean that RAF aircrew personnel were selected from ‘the finest material’? To be selected as aircrew during WWII, they had to be male, and they had to be fit, healthy, young, highly intelligent, and possess the aptitude and dedication to learn all the skills needed to be aircrew.

Victims of abuse are not selected on those same criteria. Male perpetrators of intimate partner abuse select their female targets by looking for four traits — kindness (that is, whether she is willing to put other people’s needs before her own), loyalty, dedication, and truthfulness. (I can’t comment on what traits female perps look for when selecting male targets, because I do not have enough knowledge about the minority of cases of intimate partner abuse where the genders are reversed. So far as I am aware, there are no decent studies or clinical conclusions about the selection criteria used by women who abuse their husbands.)

McIndoe also lent his weight in supporting people who were trying to get the RAF to change its regulations so that burned airmen “would remain on full pay until either ‘surgical finality’ was reached or it was considered by Medical Authorities to be in the individual’s best interests that he should be invalided from the service.” To persuade Treasury to make this change, McIndoe sent them “details of the 16 worst burns cases he had at East Grinstead together with harrowing photographs and a cost estimate for an airman’s pay during the treatment period of £3000 per annum.” It made financial sense to keep these men on full pay. Many burned airmen went back to active duty during and after their surgical reconstruction was complete. It was vital that morale remain high among all RAF airmen as Britain relied so heavily on the RAF to protect its citizens and eventually win the war. It took a while to persuade Treasury make this change, but they eventually did so.

Can you imagine that being done for people who are employed by churches and have been spiritually and sexually abused by the church leaders?

Now, over to you, dear reader.

Can you suggest reasons why McIndoe’s burned airmen were honoured and respected, but abuse victims are dishonoured and disrespected? There are multiple reasons I can think of, but I’d like you to suggest reasons, because this post is already too long.

Endnote

1 “How my heart yearns within me” is from Job 19:27b, where Job is voicing his confidence the Redeemer:

I will see him for myself;

my eyes will behold him, and not as a stranger.

How my heart yearns within me. (19:27 BSB)

For I know that my Redeemer lives,

And He shall stand at last on the earth;

And after my skin is destroyed, this I know,

That in my flesh I shall see God,

Whom I shall see for myself,

And my eyes shall behold, and not another.

How my heart yearns within me! (19:25-27 NKJ)

Robert Alter translates Job 19:25-27 like this:

But I know that my redeemer lives,

and in the end he will stand upon the earth,

and after they flay my skin,

from my flesh shall I behold God.

For I myself shall behold,

and my eyes will see — no stranger’s,

my heart is harried within me.

Alter’s note: “my heart is harried within me. The Hebrew says literally ‘my kidneys come to an end [or long] within me.’ This involves a prominent alliteration, kalu kilyotay, that the translation tries to approximate.”

***

For further reading and viewing

The Trouble with Trauma-Talk — A YouTube video in which Allan Wade, Cathy Richardson and Donni Riki discuss the problems with labelling survivors of abuse and violence with labels like “PTSD”, “trauma survivor”, etc. Much of the so-called “trauma-informed practice” actually pathologises victims, mitigates or erases the responsibility of perpetrators, and supports perpetrators’ agendas. Rather than the term “trauma-informed practice”, we need to be talking about safety-informed practice, dignity-informed practice, and resistance-informed practice. Note: the video contains a few words in which Christianity is disparaged. I think what they were disparaging was “Churchianity” and I agree with their disparagement of Churchianity. Also note that in the video, Donna Wiki, who is a Maori, uses some spiritual language with which Bible-believing Christians would not feel comfortable. I share the video because it has many helpful ideas in it, but I am not endorsing all that pertains to traditional Maori spirituality.

The Quick Sand of Stigmas — an article by Wade Mullen.

What if rape was reported like terrorism? — article by Jess Taylor.

Discover more from A Cry For Justice

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

My initial comment….and my apologies, Barb, for such a short comment on your excellent post….my expletive deleted physical and non-physical pain are very bad today. I’m planning on a longer comment on your post….in the meantime — and in no particular order — this comment will be a short one, on two of the articles you linked to in your post.

I liked only the first part of Dr. Jessica Taylor’s article, What if rape was reported like terrorism? And rather than copy-and-paste the entire section of her article that I liked, I’m only copying-and-pasting the beginning and end of the section:

From Wade Mullen’s excellent article The Quick Sand of Stigmas:

LikeLiked by 1 person

Adding on to my comment of 15th November 2023….and intentionally not copying-and-pasting and commenting on most of your post, Barb, or my comment would be way longer than it already is. 😊

In your post, Barb, you asked:

(The phrase “or community” in brackets was added by me.)

No….well, I can, but that’s not necessarily reality. 😊

In your post, Barb, you asked:

(The phrase “or community” in brackets was added by me.)

No….well, I can, but that’s not necessarily reality. 😊

In your post, Barb, you asked:

(The phrase “or community” in brackets was added by me.)

No….well, I can, but that’s not necessarily reality. 😊

In your post, Barb, you asked:

(The phrase “or other community” in brackets was added by me.)

No….well, I can, but that’s not necessarily reality. 😊

In your post, Barb, you wrote:

(The phrase “and many other people” in brackets was added by me.)

That.

In your post, Barb, you quoted from The Guinea Pig Club by Emily Mayhew:

Until I’d read this paragraph, I hadn’t realized that looking away from the facially disfigured was human instinct. I’d always felt bad when I’d reacted that way — I’d initially look away and then look back. And for some of the people I was talking to, I’d continue on with the conversation. For me, sometimes it’s hard not to look at the person’s injury, and then look back into their eyes (and keeping in mind that sometimes I look briefly look away from a person because I’m a high-functioning Asperger person)….I’m always so curious and want to ask so many questions. Not because I’m nosy….and I DO listen to their answers….I just like to find out more — about the cause of their facial disfigurement, the healing process, etc.

In your post, Barb, you wrote:

(The word “many” in brackets was added by me, replacing Barb’s word “most.)

That.

In your post, Barb, you asked:

(The phrases “or any other community” and “and many other people” in brackets were added by me.)

No….well, I can, but that’s not necessarily reality. 😊

In your post, Barb, you asked:

(The phrase “or other communities” in brackets was added by me.)

No….well, I can, but that’s not necessarily reality. 😊

In your post, Barb, you asked:

(The phrase “or other places” in brackets was added by me.)

No….well, I can, but that’s not necessarily reality. 😊

In your post, Barb, you wrote:

(The word “people” in brackets was added by me.)

That.

In your post, Barb, you wrote:

Cool! 😊

In your post, Barb, you asked:

No….well, I can, but that’s not necessarily reality. 😊

In your post, Barb, you asked:

(The phrases “or other communities” and “or their community” in brackets were added by me.)

No….well, I can, but that’s not necessarily reality. 😊

In your post, Barb, you wrote:

(The word “many” in brackets was added by me.)

That.

In your post, Barb, you asked:

(The phrase “or other community” in brackets was added by me.)

No….well, I can, but that’s not necessarily reality. 😊

In your post, Barb, you quoted from the Readers Digest:

(The phrase “and is” in brackets was added by me.)

That.

In your post, Barb, you wrote:

(The single quote marks were deleted by me, and the phrases “or other”, “and other communities”, and “and other people” in brackets were added by me.)

That.

In your post, Barb, you wrote:

(The word “many” in brackets was added by me.)

That.

In your post, Barb, you wrote:

That.

In your post, Barb, you wrote, and then asked:

(The phrases “or other places” and “or other” were added by me.)

No….well, I can, but that’s not necessarily reality. 😊

In your post, Barb, you asked:

(The bold is from Barb’s post.)

No, I can’t suggest reasons….not because I can’t, but because it (abuse victims being dishonoured and disrespected) shouldn’t be happening.

LikeLike